30th January 2024

ICCT’S FUMES STUDY RISKS MISLEADING REGULATORS AND INDUSTRY

The analysis presented by ICCT in its recently published study: Fugitive and unburned Methane Emissions from Ships (FUMES), while innovative, suffers from a range of significant methodological limitations.

The FUMES study highlights emissions challenges that have long been known and that are being actively addressed by the maritime industry and equipment manufacturers of all types. They are also the focus of a range of initiatives including the Methane Abatement in Maritime Innovation Initiative (MAMII) and the EU-funded GREEN RAY project.

The limitations of the ICCT study call into question its relevance as an input into regulatory development, specifically the determination of emissions factors used in IMO and EU regulations. They include:

- The use of an experimental airborne measurement methodology which is not verified against industry standards, nor calibrated against on board measurements.

- The fact that the analysis is based on a limited number of vessels, using older low-pressure engine technologies, in particular low-pressure 4-stroke engines. There are very few measurements from the high-pressure dual fuel technologies which have virtually eliminated methane slip and which account for more than half the LNG-fueled vessels in the new build order book.

- The inability to distinguish between individual onboard emissions sources which makes it impossible to quantify levels of methane slip associated with specific engine technologies.

- Measurements were focused on atypical vessel operating conditions and engine load factors. The study focuses on exhaust emissions from ships during port stays and manoeuvring in and out of ports, representing less than 10% of ships’ operational conditions. Related to this, the majority of observations were taken with engine loads of around 0-30%. Main engines are designed to run at loads of between 60% and 100%, the range at which they operate for the majority of voyage time. At these loads, engines show the lowest levels of methane slip.

More details are provided in the Annex.

Usefully the study proposes a range of operational measures that ship operators could use to reduce levels of slip. It also raises awareness of the need to measure potential fugitive methane emissions during the offloading of LNG cargoes from LNG carriers. In doing so the study highlights the ongoing efforts of engine manufacturers, other technology providers and ship operators to address the issues of methane slip and fugitive methane emissions.

The industry has made great strides to reduce methane slip on a voluntary basis. High-pressure dual-fuel engine technologies already exist with virtually no methane slip, and for low-pressure engines where it remains an issue, continuing innovations by engine manufacturers have resulted in levels of methane slip falling four-fold over the past 20 years.

The MAMII and the GREEN RAY initiatives started by quantifying the problem, through onboard, operational measurements of methane slip and fugitive methane emissions for multiple vessel and engine types. They are now looking at mitigation, accelerating the development of new engine technologies and other exhaust stack abatement solutions. A recent example of this can be seen in the GREEN RAY project where Wärtsilä has piloted technologies resulting in methane slip reductions of up to 56% in one of its most popular dual-fuel, low-pressure four-stroke engines. And in November 2023 MAN Energy Solutions announced that it is launching the IMOKAT II project to develop an after-treatment technology to reduce methane slip from its four-stroke engines.

In conclusion, the ICCT FUMES work highlights emissions challenges that have long been known and are being actively addressed by the maritime industry and equipment manufacturers of all types. It is essential to view the findings of studies like the FUMES project in the broader context of the full-scale operational conditions of the ships, not just in ports and near-shore operations. The advancement of technologies for both low- and high-pressure combustion should be recognised, and analysis should encompass both legacy and new technologies.

As regards regulation, it is SEA-LNG’s view that the emissions factors used in EU and IMO regulations should be based on certified operational measurements of the exhaust gas emissions from different propulsion and auxiliary engine technologies. Regulations should also allow these emission factors to be updated as engine manufacturers continue to improve the emissions performance of their new engines and technology providers develop methane abatement technologies which can be retrofitted to existing engines.

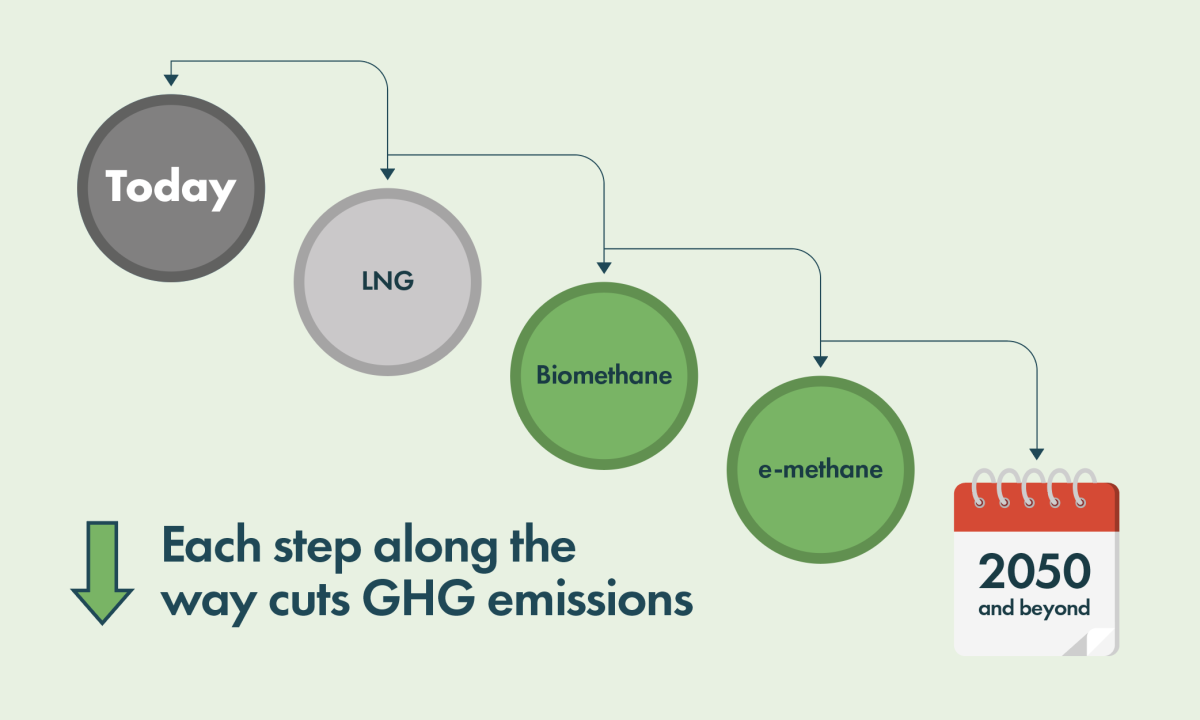

SEA-LNG remains committed to supporting the maritime industry’s transition to LNG-fueled ships, following the pathway from traditional LNG to bio-LNG products and eventually hydrogen-based LNG produced from renewable energy sources. We encourage ongoing research, innovation, and collaborations, such as MAMII, within the maritime industry to develop and implement more sustainable LNG-fuel solutions. SEA-LNG welcomes constructive dialogue and collaboration with all stakeholders to achieve our shared environmental goals.

Annex: Details of FUMES study methodological limitations

- Experimental methodology: Measurements were made using an experimental methodology, developed by ICCT and its research partners. The methodology has not been verified against a standard such as the Carbon Balance method, a 1-step calculation procedure (imorules.com). It is also not validated against direct instruments and does not have a robust and accepted methodology to convert a ppm measurement to mass flow. The use of a Toxic Vapor Analyzer, or “sniffer”, is effective for direct exhaust measurement for measuring at a fixed point. It is not considered an effective methodology for continuous sampling over a large area. Exhaust sampling without installing the probe in the smokestack of the ship does not provide credible results. The FUMES work lacks representative measurements of methane concentration and flow rate in the exhaust. Additionally, the reliability of optical methane sensors has been questioned due to the lack of significance and distinctiveness of methane’s optical absorption region. Methane has absorption bands in the same absorption wavelength regions as a number of other hydrocarbons and this can skew the results. The FUMES work lacks correlation analysis comparing drone data with in-situ measurements from the exhaust stack to establish the accuracy of the measurement methodology and technology. The deployment of the sniffer on a drone also raises significant concerns since there were no measurements taken or data present to prove the repeatability of the test results. For industrial applications, any elevated preliminary readings using a sniffer is verified through a portable organic vapour analyzer or a flame ionization detector due to the false high readings often found with a sniffer. Finally, engine load is inferred from the speed of the vessel. As no onboard parameters or measurements were taken a methodology was used to police and inspect vessels from aerial assessment. Additionally, the measurements taken at the “sweet spot” of the ship exhaust plume represent an engine state several minutes prior to real-time where engine load is inferred (and port movements are not in a steady state).

- Limited number of vessels: Measurements were made on a limited number of vessels mainly using older low-pressure engine technologies, in particular low-pressure 4-stroke engines. For the high-pressure dual-fuel engines which have minimal levels of methane slip and which make up the majority of the LNG-fueled new build order book, only four observations were taken. It is unknown how many auxiliary engines contributed to the exhaust plume in these observations.

- Inability to distinguish between onboard emissions sources: The exhaust gas cloud sampled by drones and helicopters was made up of emissions from multiple engines onboard meaning it is not possible to isolate a measurement for a single main engine type and quantify the associated methane slip. The ways in which different engines are operated complicate emissions attribution. For example, during harbour movements (pilotage) main engine loads are much lower and multiple auxiliary engines are running at low loads to cover navigational safety requirements.

- Atypical vessel operating conditions: The project only assesses a very narrow percentage of the exhaust emissions associated with a full ship voyage. It primarily focuses on exhaust emissions from ships during port stays and manoeuvring in and out of ports, representing less than 10% of ships’ operational conditions.

- Atypical engine load factors: Related to Point 4, observations were taken with engine loads all below 70%, with the majority around 0-30%. Main engines are designed to run at loads of between 60% and 100%, the range at which they operate for the majority of voyage time. At these loads, the engines are running at high temperatures and with stable operation and show the lowest levels of methane slip.

“The analysis presented by ICCT in its recently published study: Fugitive and unburned Methane Emissions from Ships (FUMES), while innovative, suffers from a range of significant methodological limitations."

Steve Esau, COO, SEA-LNG